- Home

- Nadia Terranova

Farewell, Ghosts Page 2

Farewell, Ghosts Read online

Page 2

When I left Sicily, my nose was the first thing that changed. It had grown more and more congested, hostile and scornful toward the scant oxygen of the capital, saturated with cement and smog; then my skin had changed, because of the chalky water that came out of the faucets and the exhaust from the cars; finally my back had changed, curving unnaturally as I got on and off buses and trams. Thus I had been Messinese and become Roman, had been a girl and become an adult and a wife.

“As long as I was here my breathing was fine,” I insisted.

In my mother’s eyes a grim satisfaction appeared; meanwhile I was tired and getting sleepy, so I asked if we could have dinner early, and afterward, finally, I shut myself in my room alone.

With every movement, a fine dust rose: from the pale wood shelves when I grazed the spines of the books that filled them, from the pillow and the framed prints I ran my finger over, from the pink cloth bedspread I moved aside to get into bed. The mattress was too small; to be comfortable I would have had to cut off my feet at the ankles. The idea made me smile; I lay down, avoiding pillows and sheets. I couldn’t have had any memory of many of the ages that surrounded me, but I knew the story of the wicker basket they’d brought me home from the hospital in when I was born, along with the legend of the blue wool blanket given by a cousin to celebrate my birth; my mother despised this cousin because of a dull, stocky boyfriend, with short fat thighs, who—she often repeated with a gesture of disgust—had come to the hospital in a leather jacket, and, since she had just given birth, that vulgar odor of the secondhand had nauseated her. My mother, accustomed to project onto objects what she thought of those who had touched them, adored the basket and hated the blanket; between the first, sitting on the floor, and the second, on the night table, I would have to seek my place for the night.

There were still old clothes of mine in the drawers, I pulled out a T-shirt and closed my eyes, so as not to feel the assemblage of all the things.

First Nocturne

I wake with mites in my lungs. Anxiety or asthma, I shouldn’t have agreed to sleep here, returning is always a mistake. Dust or sea air, I can’t breathe, I went to sleep too early.

I’m a grown woman pinned to the darkness by her childhood dolls. Other families would have kept one, at most, in mine we’ve kept them all. The one sitting in the basket, in place of my newborn self, blinks in the dark.

My classmates’ houses were so light that when I entered I imagined they would lift off from the ground; the owners had the freedom to leave them at any moment, while my mother and I struggled to walk in ours, chained to the objects we didn’t throw away. We kept everything, not to celebrate the past but to propitiate the future: what had once been useful could be useful again, you had to have faith in objects and never absentmindedly throw them away. We saved them not to remember but to hope; all the objects performed a role and launched a threat, and now they’re around me, looking at me.

The striped waterproof playsuit from when I was three, put away for the children I haven’t had. The trousseau and the tarnished silver and the chandeliers wrapped in white cloths, for married life and the apartment I didn’t buy in Rome. The girls’ boxing gloves, which lasted for a few exhausting lessons in a rubber-floored gym, until I understood that I’d be trained for everything but defending myself: at most I would learn not to suffer from being the weakest. And dozens, hundreds of objects of every shape and size, puppets, books, colored plastic toys, wooden combs, boxes of clothes: I saved and submitted to the will to save, I hoped and submitted to the will to hope.

The room is now saturated with unused hope.

Through the shutters comes a puff of wind, the sirocco has grazed the dry leaves of the aloe on the balcony that died in the heat. If I close my eyes memories are staged on that balcony.

One. Peeing on the plants, one night when I came home drunk after a bonfire on the beach with friends, because I didn’t have the energy to cross the hall to the bathroom.

Two. At dawn I heard the sound of horses in the street, I thought I was dreaming that a coach or carriage had gone by; on waking I told my mother, who nodded but didn’t believe me. As I discovered, looking out one night, the sounds belonged to clandestine races: the delinquents from the adjoining neighborhood closed the streets and transformed them into a mafioso palio, where people flocked to bet on underage jockeys and moribund horses. My fragile neighborhood, stuck between the middle-class apartment buildings of the center and the working-class projects on the hill, invaded alternately by one and the other, was born and grew up apologizing for its anonymity. I close my eyes tighter; that is an ugly story.

Three, fear. One night after I’d decided to leave, and was nearly done with my packing, I went out on the balcony to smoke. A sound of footsteps in the street made me look down: a boy in a hooded sweatshirt, hands hidden in his pockets, stopped, looked right and left, squatted down suddenly to leave something under a car, and ran away. The neighborhood, at that time, had been colonized by small-time dealers, who took advantage of the fact that, because of the burned-out streetlights, the sidewalks were always dark. I went inside, closed the outside shutters, the inside shutters, the curtains, exaggerating the fear: I was afraid that if that kid had looked up and seen me on my balcony he would at the very least have murdered me, and consoling myself, I repeated that I would leave, leave, leave.

Four. There has to be a fourth memory, I hope it’s slight. No use. Night brings proximity to stinging memories, insomnia, and desperation. It might help to think about sex, if I could concentrate.

Sleep returns along with my mother’s commands. Don’t go out on the balcony, it’s dangerous, we’ll have to deal with redoing the façade soon, too. It’s not your problem anymore, I answered, avoiding her future, since you’ve decided to sell.

The White Light of the Strait

I woke with the heat and voices of the morning, and looked for Pietro’s foot; sticking mine out into the space, I remembered that I was in the little bed, was alone, and hadn’t yet written to him. My husband and I didn’t like to talk on the phone when we were apart; we’d made a pact not to intrude on each other, to act so that our lives, once they were distant, could take different routes, all possible routes. “Good morning,” I wrote, sleep making my hands sluggish, as I tapped on the phone with half-closed eyes. “Everything fine here, hope so for you.” The lack of a question mark was the signal: You’re not obliged to answer, I know you’re there.

On the street, two floors below, a motorbike with a broken muffler was slowing down, a girl was calling someone in a loud voice, from the balcony opposite came the sound of carpets being beaten in the sun. In the room the light absorbed the excess dust, the outlines of objects became fixed, thoughts returned to order. The memory of insomnia got me up immediately, frightened: it was better not to delay, not to stay imprisoned in bed after such a difficult first night.

I crossed the hall barefoot, in my underpants and the T-shirt I’d slept in. In the kitchen, a sheet of graph paper was stuck in the spout of the coffeepot on the unlit stove, bearing my mother’s prescriptive writing and the imperative of a single word: “Light.” Passing her room, I had glanced in and seen that it was empty, but I didn’t need proof; I knew very well that we were alone, the house and I.

Whenever I stayed alone in an unfamiliar apartment, I moved in a state of paralysis, cautiously obedient, under the severe gaze of the absent owners. If they had told me to take off my shoes, I walked barefoot, if they were afraid that something would break, I didn’t even touch it, as if they really could reproach me for violating their rules. Mindful of how tense this made me, I tried never to be a guest, and when I traveled I always chose anonymous hotels, beds with carmine quilts and panoramic watercolors over the headboards, neutral, uninvasive rooms, to which I could bring my nightmares and my insomnia. I sought relief in being alone and yet I never was alone: as far back as I could remember I never had been, especially in

the house in Messina. There, until I was thirteen, my solitude had been inhabited by my mother’s parents, who died before I was born: we had inherited the house from them, and it took them a long time to resign themselves to leaving it. They reappeared once a year, on the Day of the Dead, but I had the impression that they were always watching over it, even in my most embarrassing moments, when I was in the bathroom, or lost in secret fantasies.

In that same kitchen, Sara, the friend of my adolescence, had told me she had had sex with two boys at the same time; by then our bond had nearly dissolved, we were approaching one of those inevitable separations that mark friendships before adulthood, each the other’s witness of years we’re ashamed of and would like to forget; that afternoon, one of the last, when neither of us was quite eighteen, I envied her for what I would never have had the courage to do. I was sure that if I tried to have fun, the dead of my family would reappear at the foot of the bed to stare at me in silence; the dead are envious judges of all the actions they can’t perform anymore, of the errors they can no longer commit, of the entertainments of the survivors. My mother’s dead had remained in the house with the precise intention of knowing me, the granddaughter born after their passing. My grandfather, anticipating his own stroke shortly before it arrived, had brought the car to the guardrail and died on the highway, with the four emergency arrows flashing; my grandmother had developed cancer a few months after her husband died, and the house had thus ended up in the hands of their only daughter, my mother. The old people came back to see us the night between the 1st and 2nd of November, when I set bread and milk out on the table and the next morning found the milk half drunk and the bread half eaten, as well as an envelope with a banknote, the hard pure-white almond cookies in the shape of the bones of the dead that I gnawed on, hurting my teeth, and the marzipan fruits that were left uneaten, because they were nauseatingly sweet, and just looking at their perfection was enough to satisfy: sculpted and colored to resemble a prickly pear, a bunch of grapes, a slice of watermelon. That it was my mother who put on the clothes of the dead and performed the fiction didn’t matter, didn’t make that nighttime passage less true. That was death as I’d known it up to the age of thirteen: a straight, infinite line that had to do with heredity and the inescapability of time, a place people don’t return from except once a year for a celebration, an unfortunate but essentially fertile event. That’s what it was, and it didn’t frighten me.

Then one morning my father disappeared.

Not like my grandparents, already old before I was born, not like an accident or a heart attack that ends a life. Death is a full stop, while disappearance is the absence of a stop, of any punctuation mark at the end of the words. Those who disappear redraw time, and a circle of obsessions envelops the survivors. My father had decided to slip away that morning, he had closed the door in the face of my mother and me, undeserving of goodbyes or explanations. After weeks of immobility in the double bed, he had risen, turned off the alarm, set for six-sixteen, and left the house, and he hadn’t returned.

At seven-fifteen I got up for school—I was then in the last year of middle school—and I went to the bathroom to wash, crossing the hall as I had done since I was born, as I crossed it still as an adult: underpants, T-shirt, bare feet, and three-quarters of me still snagged in the night. On the kitchen table was the milk and the biscuits, but passing the bedroom I had felt an absence (the insufficiency of a place, its not being enough: not even the room-prison had been able to restrain him). For a long time my father had huddled between the sheets, with the psychic grief no one talked to me about, but I intuited a lot. I knew that he was there, and that after school I would pretend to have lunch with him; I knew that he wouldn’t eat and I knew that I would give my mother and myself a different version of the facts. But in my not-looking that morning was a perception of irrevocability.

I’ve often wondered if that wasn’t a story I invented later, adding what I discovered in the afternoon, that my father had gone, but that false sensation would still have been truer than the truth. Memory is a creative act: it chooses, constructs, decides, excludes; the novel of memory is the purest game we have. Coming home, I noticed from the street the new furor that animated the house, I heard it as soon as I turned the corner, like my mother’s crying. My mother was calling my father’s name, and as soon as I entered she attacked and suffocated me: Your father has gone, your father has left us. And even though at the police station they told us we had to wait seventy-two hours to report his absence, she didn’t want to wait even a day to report to me what she knew, what we both knew: a depressed man had consciously and forever left life and the two of us.

So at thirteen I became the daughter of someone who had disappeared: the real dead die, are buried, and you weep for them, while my father had vanished into nothing, and for him there would be no November 2nd, no calendar—he would no longer have one, and my mother and I wouldn’t have one, either. That year we didn’t celebrate the dead and the grandparents didn’t come to see us. In compensation, on November 2nd precisely I got my first period. As for the house, it had become the sacred place my father might return to at any moment, and now my mother wanted to sell it. What would become of him, alive or zombie or ghost, the day he showed up at the door, reclaiming his half of the bed and his place at the table?

The smell of burned coffee brought me back to the present, and I fixed my eyes on the kitchen wall, the only wall of the house adjoining another apartment. In the past a noisy family of evangelical Christians had lived there; at night my mother and I heard them through the wall, singing, while, unmoving on the couch, like part of the furniture, we stared at the television, gripped by our fiction of placidity, as if there had always been only the two of us, the two of us period. They’re singing, I thought, staring at the TV news. I forced myself to imagine seven people around a table concentrated on praising God, brothers, sisters, a mother, and then that other adult, the father, the word that was now so painful.

“You burned the coffee,” my mother said, entering the kitchen with a bag of vegetables.

I thought: My father disappeared twenty-three years ago.

“I got the coffee ready so you just had to turn it on.”

I thought: He disappeared into nothing and after the first days we never talked about it.

“I put a note in the spout the way your grandmother did with me.”

I thought: Why didn’t we talk about it anymore?

“Have you been up long?”

I thought: Why didn’t you talk about it anymore?

“The workers are coming at eleven for the final assessment.”

I thought, looking at my legs under the T-shirt: She’s telling me to put something on to cover myself.

“Have you started choosing what you want to keep?”

I said: “You mustn’t touch any of my things.”

Twenty-three years have passed, I thought. What have I done in those twenty-three years, where have I been, who have I listened to. There could be beside me a stranger of twenty-three born the day he left, and beside her the child of thirteen, stopped forever at that age. I looked at the girl, I looked at the child. The child wasn’t growing up. She would never grow up. She would continue to stare at me, motionless, the whole time I was in the house.

“They’re here!” my mother called from the door.

I put on some green cotton pants that had once belonged to a gym uniform and looked for a mirror to straighten my hair. I found a shard of rough glass with the drawing of a flower on the side. I’d painted it with my cousins, and then we set up a stand on the seaside road to sell things. We sold perfume bottles belonging to our mothers, aunts, grandmothers, a few mirrors, bracelets—all dusted, washed, and decorated by our adolescent hands. At that time I carried in my chest a burning, unexploded grief, a small red-hot sphere.

Looking in the mirror, I smoothed my hair with my hands, shifting it to the

side, and the telephone vibrated. “How’s it going?” the screen asked. “Let me know when you can.” I seemed to feel the roof collapse another little bit.

I put the telephone under the pillow and left the room.

In the front hall, a boy of twenty and a father of sixty were talking to my mother. “Signor De Salvo,” she introduced them with a smile, “and this is his son Nikos. The mother is Greek.”

The slight intoxication in my mother’s voice suddenly made us all exist: me, them, the walnut prie-dieu, the umbrella stand covered with plaster dust.

“Greek, interesting.” Throwing words together randomly I led that father and that child toward the hole in the living room. “Greek from where?”

After more than two decades, another father was entering our house, employed by my mother. The small sphere began burning in my chest.

“From Crete,” Nikos answered; he bumped into a pile of old board games in a corner and Snakes and Ladders fell on the floor. “Watch out,” I got angry as I followed the pieces that rolled under the chairs, and we bent down to pick them up. “Wait, I’ll do it.” I had used lei, the formal “you,” and he had responded with the informal tu: I would never learn to impose the authority of hierarchies.

Meanwhile the father explained to my mother the difference between thermal and acoustic insulation and my mother answered that we didn’t have a noise problem, only a water problem. Nikos and I, once the last piece had been picked up, closed the game box.

My mother was lying about the noise. After my father disappeared, during the long afternoons at home I heard a child shoot a glass marble against the walls, wait for it to come back, shoot it again, so that it rolled along the floor, and start again. At first I thought it was one of the children of the evangelicals, but the noise wasn’t confined to the common wall; I heard it sometimes in the hall or the bathroom. Years later, in a puzzle magazine, on the page devoted to “things you might not know . . .” I discovered that the specter with the marble infested various houses in Italy, and was in reality the gurgling of old pipes.

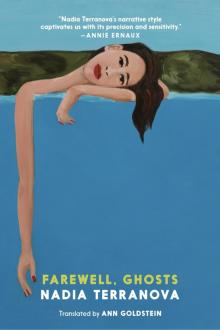

Farewell, Ghosts

Farewell, Ghosts